Murder, Tsunamis, Vigilantes and Pirates: Four Filmmakers on going to Extremes to Shoot their Passion Projects

Canon Canada

There’s an inherent dichotomy in making documentaries. On the one hand, cameras are more advanced, nimble and affordable than ever before—so it’s never been easier to be a filmmaker. On the other hand, documentarians are going to greater lengths to capture unseen footage. Directors can spend years cultivating and sourcing subjects, they travel to treacherous locations to tell a story and they collect hundreds of hours of interviews.

Here, in their own words, four documentarians describe coming face to face with the most challenging shoots of their lives.

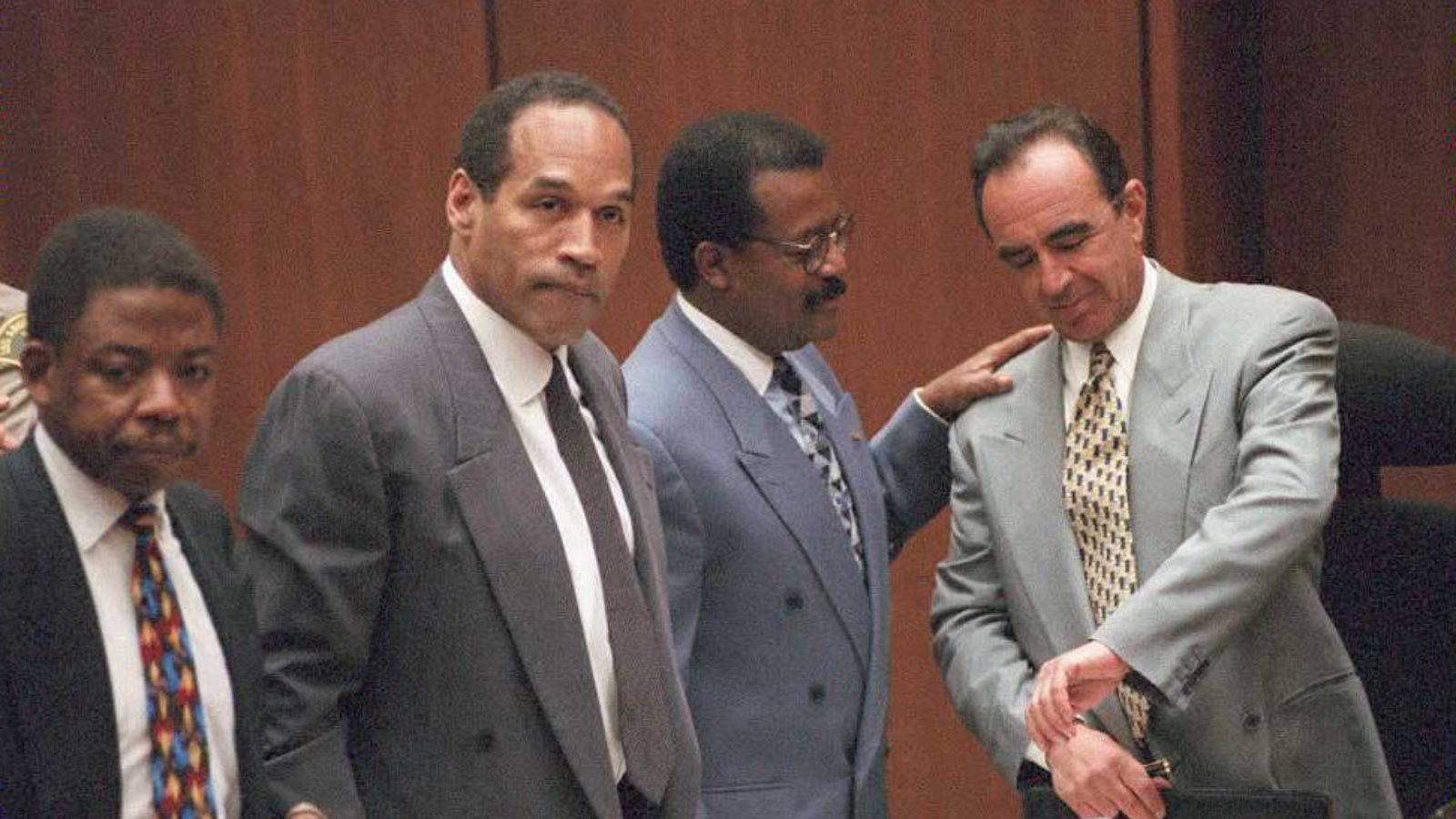

Ezra Edelman

Director of O.J.: Made in America, the eight-hour documentary about the 1995 murder trial of O.J. Simpson. Screened originally on ESPN, it won the 2017 Academy Award for best documentary.

Shot on: Canon Cinema EOS C300

In his own words: “There was a need and an ambition to tell O.J.’s story with some sort of thoroughness,” Edelman told Wired. “I was interested in telling the story of what happened to him after the trial; at the same time, I wanted to tell this other story about the relationship between the black community and the police department in LA, and that that was going to inform this greater story about race in America. Then there was this story about him as a cultural icon that existed on this other level. But it all came back where we were going with the trial. It feels like the ultimate American Studies paper.”

He and his colleagues created a billboard to keep track of the scores of interview subjects. “It was organized chaos,” Edelman describes. “I was looking for first-person voices: people who lived through this history at every point, whether it’s O.J.’s football career or the LAPD. When you look at the people who are the most important and impactful people in the film, you’re like ‘I didn’t know who any of these people were.’ I was standing on a train platform somewhere in Connecticut, and [producer] Tamara [Rosenberg] called me up and she was like, “So I just talked these guys, I dunno, they were a couple of O.J.’s childhood friends…” and I had never heard of them, but that’s exactly where this whole thing comes together. Every time that happens, it’s like a small victory.”

Edelman and crew spent two years on the project, gathering 800 hours of footage—including from 72 new interview subjects.

Courtesy Lucy Walker.

Lucy Walker

Director of Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom (2011), nominated for an Academy Award for best short documentary, about the aftermath of the devastating tsunami in Japan.

Shot on: Canon EOS-5D Mark II

“We drove the narrow road to the great north to the Tōhoku region where the tsunami had hit. Nothing prepared us for being in that landscape. Photos aren’t three-dimensional. The area of devastation was so immense, and so little work was going on yet to clean up. I guess I was expecting a smaller disaster zone with more people. Instead the damage stretched for miles around, and there were only very occasionally other lone human beings climbing around over the debris in this post-apocalyptic dystopia.

“To my surprise many people would approach us, and were very happy to share their story. That was the best part. There were too many worst parts: seeing blasted vehicles with keys in the ignition, or seeing that someone had been inside, the signs painted on cars and houses to say that bodies had been found inside, the terrible smells that emanated here and there. The radiation was a big concern: I was well-informed about the risks thanks to my work on Countdown to Zero, but every time we ate, or every time it rained, or every time we washed, we were thinking about how not to be contaminated.”

Courtesy Matthew Heineman.

Matthew Heineman

Director/cinematographer of Cartel Land (2015), a documentary about vigilantes waging war against drug cartels in Mexico.

Shot on: Canon EOS C300

In his words:

“I’d never been a war reporter,” Heineman told The Guardian. “My last film was about healthcare in America, and I’ve never been to a conflict zone in my life until my dad sent me a clipping about the self-defence militias in Mexico. Immediately, when I read it, I knew I wanted to create a parallel story about vigilantes on both sides of the border.

“But then I just got deeper and deeper in. I got access I never thought I would, and felt a huge responsibility to tell this story. From the first moment I set foot in Mexico, I wanted to get into a meth lab. Most of the meth consumed in the US comes from Mexico, and much of it from Michoacán. Everywhere we went, I asked people: do you know somebody who is connected? But for four months, we failed. Then, finally, we got a call: be in this town square at 6 p.m. We were met by masked men, who drove us through towns, smaller towns, and then fields, until we stopped—and a separate car arrived to drive us.

“When we arrived, it was night-time. I don’t shoot with lights, so I couldn’t believe that I had come this far, and wasn’t able to see anything with my camera in the darkness. But then the head chef started showing me the lab with a flashlight, and with this flashlight, I lit the scene.”

“I was not mentally prepared for the shootouts, torture, and other intense moments that I experienced first-hand. But far harder, and scarier in a way, was listening to the story [of a woman who had been forced to watch the brutal murders her husband and four others]. Not just the fact that the cartel would do this, but the sadism of her punishment was madness.”

Jerry Ricciotti

Cameraman for the HBO series Vice, which often travels to dangerous locations to tell stories not covered by much of the mainstream press.

Shot on: Canon Cinema EOS C300

In his words:

“We went up the Niger River delta in Nigeria to do a story about oil pirates,” Ricciotti told Newsshooter.com. “These guys continue to break into Shell Oil’s pipelines across the delta where they live. They’ll take the oil out of the pipelines and build these large, basically like moonshine distils, where they refine oil themselves. We weren’t sure if we’d have power there so we brought three to four days’ worth of batteries and cards, and camped up there to go out and find these guys. And we did. We found them in the middle of the night, so we shot with a small light panel and a shoulder rig on a Panga Boat as we sped along the river, doing pieces to camera the entire way as we looked for the indication of oil pirates, which are big plumes of smoke flaring from their oil stills.

“Once we got there, we had to walk in a foot of sludge, which is basically a combination of mud and oil that had been discarded by the guys on a daily basis. They’ll refine gallons and gallons of oil but a lot of that gets discarded around them, so they’re throwing this oil out all over the place. You’re standing in big knee high rubber boots and as the oil is being refined it’s generating a lot of smoke. It’s really a dangerous environment because that smoke can catch fire and the whole place can go up in flames. Of course, you’d like to have a tripod but you can’t, so you find yourself kind of balancing with one hand out trying to keep your balance and the other hand shooting as you move across a pretty explosive terrain.

“And the whole time monitoring audio and pulling focus, so I was really happy with the camera. You didn’t need a heavy rig on your shoulder and you didn’t have to look through it all the time. The precision focusing and the low light capabilities meant it was the perfect camera for the job.”